The town of Dorking has produced many eccentrics, but none, not even the man who married his horse, can compare to Mr D. and his thermometer. For seventeen years, from 1721 to 1738, this Mr D. did nothing but record the temperature, every two hours, never missing so much as a day. At the end of the seventeen years he sent his records to the Royal Society, with the request that they be published “in the interest of advancing science.” When they were returned without comment, he became disillusioned with the weather, and set out in search of other temperatures he might measure.

His first venture, at Bath, went badly. There he dipped his thermometers into the waters, staring fixedly at it all the while and ignoring the shrieks of the lady bathers, who were in a partial state of undress. He tried to reason with them, explaining that what he did he did for science, and not even stopping to look at all the bosoms bobbing along the surface of the water, he continued with his measurements. He was asked to leave the town, and threatened with a whipping should he ever return.

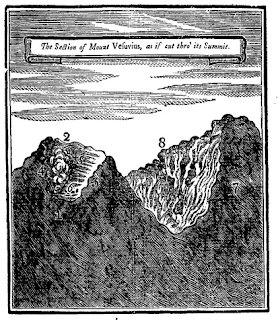

He next got it into his head that he would measure the temperature at Mount Vesuvius. His friends pleaded with him not to go. “Isn’t it enough to know that it’s very hot there?” they asked. “Yes,” he replied, “but do you know how hot?” And so against their wishes he set out for Naples. There he hired a team of donkeys to take him all the way to the top of Mount Vesuvius. But halfway up he was attacked by brigands, who robbed him of all his clothes. But he still had his donkeys and his beloved thermometer, and undaunted, he trudged on, naked as the day he was born. He could just see the rim when he was next attacked by gypsies (who are very numerous in that part of the world). They rode off with his donkeys, leaving him with only his thermometer. Still he trudged on, and reaching the very top he made a complete circuit of the rim, stopping every six paces to take the temperature. The heat was unspeakable and to his surprise he found that he did not miss his clothes. In fact, he entirely forgot about them and it was in a state of complete undress that he began his descent down the mountain.

As luck would have it, the first building he saw was a convent. He entered and the nuns started shrieking. Soon, however, they began to perceive the advantages of having a naked man among them, and it was some time before they at last agreed to furnish him with clothes. Being nuns, however, the only clothes they possessed were nun’s habits, and it was in this dress or none at all that he would have to continue his journey.

Mr D., being a good Protestant, was torn. “Which is the bigger sin,” he asked himself, “to dress up as a nun or to wear no clothes at all?” And in truth, both seemed equally wicked. But the longer he pondered this question, the more the nuns pestered him, until he was almost too tired to move. At last he made up his mind: he would leave dressed up as a nun, if only to get some peace.

It was in this guise that he boarded the next ship bound for England. But even then his troubles were not over. The sailors, being good Protestants and men besides, took their turns raping him, and when they discovered that he was one of them, an Englishman and a good Protestant, they gave him a sound beating for having deceived them. More dead than alive, in rags and missing an eye and most of his teeth, he arrived back in England, where he was chased and set upon wherever he went. But still he trudged on, at last arriving, in a state miserable beyond description, back in Dorking. And from that day on, he never troubled himself again about the temperature, simply accepting, as other people do, that it is either hot or cold or somewhere in-between.